The spherical harmonic Y l m can then be cancelled from the two sides of So operating on ψ E l m ( r, θ, ϕ ) = R E l m ( r ) Y l m ( θ, ϕ ) it will give ℏ 2 l ( l + 1 ) / 2 m r 2. Now, notice that in the Schrödinger equation above, the angular Ψ E l m ( r, θ, ϕ ) = R E l m ( r ) Y l m ( θ, ϕ ). Therefore that of the Y l m ’s, so the solutions must be of the form

The angular dependence of these eigenkets is Since the potential is spherically symmetric, the Hamiltonian H commutes with the angular momentum operators L 2, L z so we can construct a common set of eigenkets Factoring Out the Angular Dependence: the Radial Equation Writing out ∇ → 2 explicitly in spherical coordinates: We’re ready to write Schrödinger’s equation for the hydrogenĪtom, dropping the r suffixes in the second equation above, and If the proton is replaced by a deuteron (heavy hydrogen). The electron mass and the reduced mass, but it should be noted that theĭifference is easily detectable spectroscopically: for example, the lines shift Heavier than the electron, we will almost always ignore the difference between

Mass of hydrogen atom free#

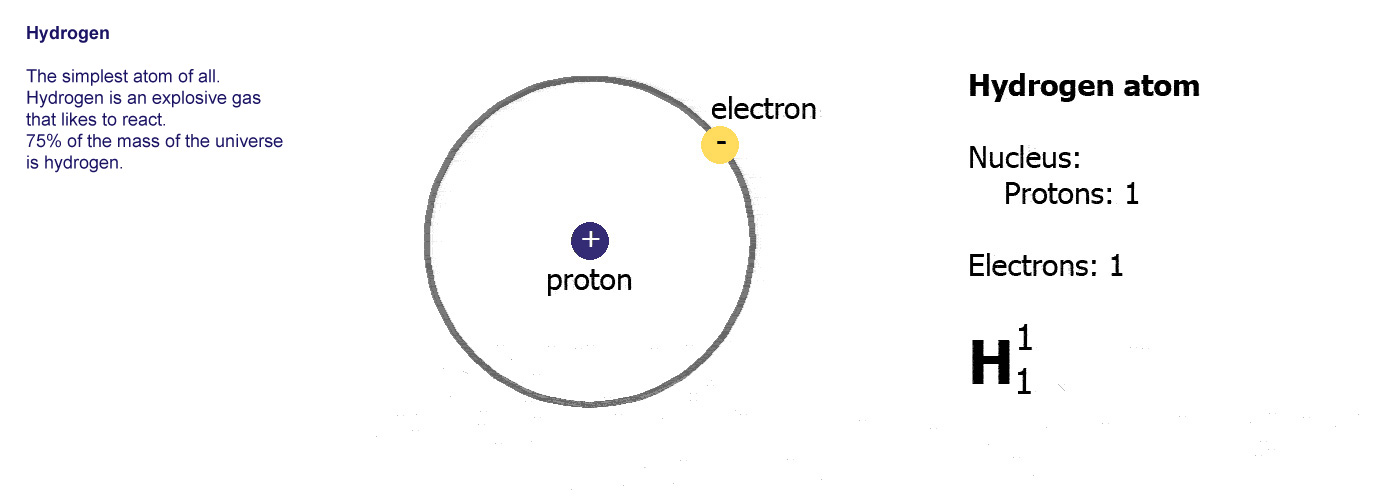

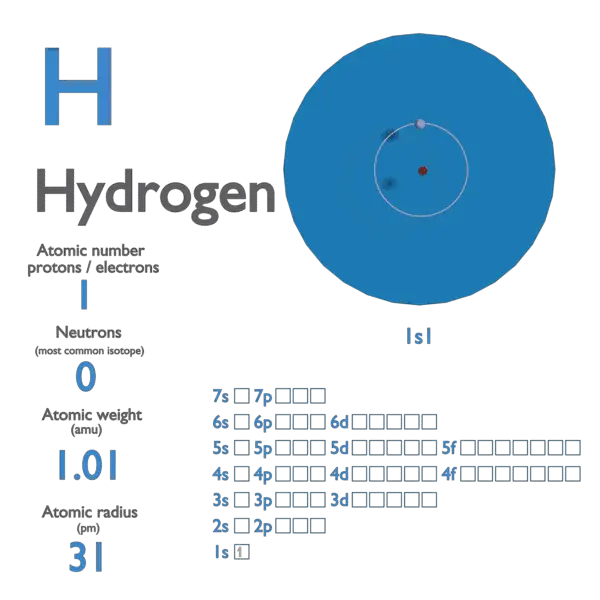

(of course) just that of a free particle, having a trivial plane wave Note that the motion of the center of mass is ( − ℏ 2 2 M ∇ → R 2 ) Ψ ( R → ) = E R Ψ ( R → ) ( − ℏ 2 2 m ∇ → r 2 + V ( r → ) ) ψ ( r → ) = E r ψ ( r → )Īnd the total system energy is E = E R + E r. Transforming in straightforward fashion to the variables r →, R → Schrödinger’s equation becomes It isĬonvenient at the same time to denote the total mass by M = m 1 + m 2 , and the reduced mass by m = m 1 m 2 m 1 + m 2. So R → is the center of mass of the system. Most natural position variables for describing this system: since the potentialĭepends only on the relative position, a better choice is r →, R → defined by: Writing the masses of the two particles as m 1, m 2 Schrödinger’s equation for the atom is: The electron, interacting via the Coulomb potential V ( r → 1 − r → 2 ) = e 2 / r, The hydrogen atom consists of two particles, the proton and Using these values gives an atomic mass of 938.8 MeV/ $c^2$ for hydrogen, but the measured atomic mass of hydrogen is 939.0 MeV $/c^2$.Michael Fowler, UVa Factoring Out the Center of Mass Motion Proton mass is 938.272 MeV/ $c^2$, electron mass is 511 keV/ $c^2$ and the ionization energy of hydrogen is 14 eV.

The calculation does not add up, however.

the ionization energy of hydrogen is featured. However, as there is only one nucleon in hydrogen, the contributions to B do not feature a any term from nuclear binding, only the binding energy of the single atomic state in hydrogen, i.e. If I take the hydrogen atom, and try to predict its mass this way, I find, unsurprisingly And where B is the net binding energy of a nucleus. Where subscripts $m_p$, e and n mean proton, electron and the neutron masses, respectively. Let me elaborate: the atomic mass of some nucleus $^A _Z X_N$ is defined as It appears that the mass of the simplest of the examples, hydrogen is not correctly produced, yet I cannot put my finger on what is the reason for this. After spinning around the atomic mass equation for calculating neutron separation energies, I have run into somewhat of a conundrum.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)